As telehealth transitions from a nice-to-have benefit to an essential form of care delivery, payers will have to make some adjustments in order to permanently integrate telehealth coverage expansions.

– Telehealth is metamorphosing and payers will have to take steps in order to permanently integrate telehealth coverage as a key form of care delivery.

When the coronavirus pandemic struck, Donna O’Shea, MD, chief medical officer of population health management for UnitedHealthcare, and other leaders at UnitedHealthcare watched as the payer’s telehealth claims shot up ten times higher than the previous year’s numbers.

It is now a familiar narrative, how the pandemic that swept the nation was a precursor to the largest surge in telehealth utilization in American healthcare’s history. Telehealth uses that might have taken years, perhaps decades, to adopt were integrated into the healthcare delivery system seemingly overnight.

“The COVID-19 pandemic may prove to be a watershed moment for the healthcare system, prompting a surge in the use of virtual care,” O’Shea told HealthPayerIntelligence in an email interview.

Now, payers face a new crossroads with telehealth. As telehealth waivers expire and utilization stabilizes as in-person visits return, the healthcare industry may be tempted to return to a pre-COVID mindset about telehealth.

But that may not be able to happen.

“Going into COVID, telehealth had become a nice-to-have benefit for employees who needed convenient care for minor issues and it wasn’t built with an orientation to be much more than that,” Mike Thompson, president and chief executive officer of National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions, told HealthPayerIntelligence. “What we have found since COVID is that, when telehealth went mainstream, the expectations went way up. As we go forward, I think it becomes more of an integrated strategy. It becomes an expectation that this is a modality that providers will use.”

A shift is coming, Thompson and O’Shea confirmed. Payers will need to support the healthcare system’s transition from viewing telehealth as an “add-on” benefit to a permanent, integrated solution.

There are a couple of questions that payers need to ask in order to develop long-lasting telehealth strategies. First, what telehealth services are the most sustainable long-term? Second, what payment strategies are appropriate for these services? The answers may vary across payers, but, overall, some themes are emerging.

What services can be provided virtually on a long-term basis?

Payers and providers have implemented telehealth for a broad range of services. However, to integrate telehealth permanently into health plan structures, payers need to assess which services are best suited to telehealth.

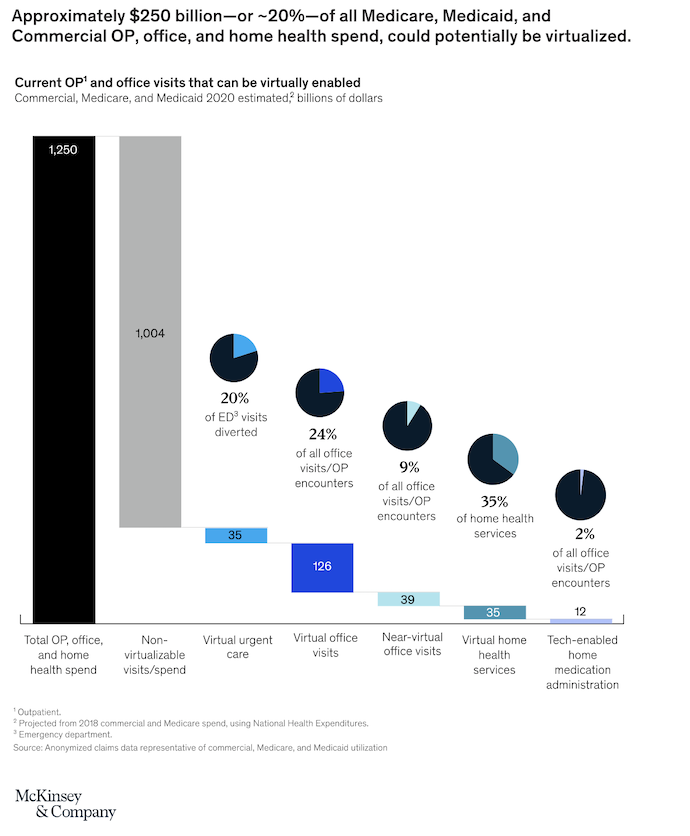

An early analysis of COVID-19 telehealth utilization published in May 2020 found that approximately 20 percent of all Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial outpatient, office, and home healthcare spend could transition to virtual care. This equates to around $250 billion worth of care.

Specifically, 35 percent of home healthcare, 24 percent of office visits, and 20 percent of emergency department visits could be virtualized, the report asserted.

In some areas of healthcare, payers can build on progress made before the pandemic struck.

“One of the most exciting spaces and where we’ve seen a lot of the initial growth is going to be in behavioral health,” said Thompson.

Telehealth was already being integrated as a care delivery platform for behavioral healthcare before the pandemic. With the shutdowns and the increase in behavioral and mental healthcare demand, the need to use telehealth for these conditions was inescapable.

The coronavirus pandemic took behavioral telehealth one step further.

“You don’t become a telebehavioral health provider or a regular provider. Increasingly, practices are both,” said Thompson.

The pandemic has confirmed for Thompson—and many in the payer industry at large—that many members now view telehealth as their preferred care delivery model for behavioral healthcare.

Source: McKinsey & Company

Partly, members enjoy the convenience of not having to travel to a provider’s office and still being able to connect virtually. It also diminishes the likelihood that members will experience stigma, Thompson pointed out, since they do not even have to walk outside their homes in order to see their provider.

However, other uses for telehealth have emerged due to the pandemic and the payers must identify which uses should become more permanent.

“Payers are starting to bifurcate a little bit between telehealth as a triage tool versus telehealth as a subacute or medication maintenance or check-in platform for patients to just see their providers,” Tim Epple, principal at Avalere, told HealthPayerIntelligence.

Early data indicates that using telehealth to triage is an effective way to reduce healthcare spending, he said. Ensuring that members are accessing the right level of care and not accruing unnecessary costs through avoidable trips to the emergency room is possible by simply offering a 24/7 triage telehealth platform for members to contact.

“The triage point is where you can see really clear, immediate savings,” Epple added.

In fact, in 2018, AHIP estimated that payers save over $6 billion annually by promoting remote care and telehealth options that allow members to access care from home instead of going to emergency or acute care sites.

Whereas the pandemic has tested and proved telehealth’s triage capabilities, for other telehealth uses payers may need to gather more long-term data to determine if telehealth should be permanently integrated into those care delivery processes.

“It’s going to take a little bit longer for payers to really understand, how does that potentially greater adherence to medication management hit our bottom line? Do we think doing physical therapy or other historically in-person services virtually are actually meeting the bill in terms of outcomes?” Epple said.

Thompson emphasized the ways in which telehealth could develop a more permanent, widespread role in primary care.

“We should put a lot more emphasis on primary care,” he said. “As part of putting more in some primary care, we should be building in virtual integrated care.”

O’Shea at UnitedHealthcare agreed.

“While virtual care has historically helped address minor medical issues, including allergies, pinkeye, fevers, rashes and the regular flu, we are starting to see an expansion of the types of services being offered remotely,” O’Shea noted. “The most promising developments include virtual care resources to help expand access to primary care and support chronic disease management, behavioral health, and certain types of specialty care (dental, vision and hearing).”

O’Shea emphasized that acute or follow-up virtual care can be essential for members who have complex conditions that prevent them from being able to visit the provider’s office in person.

Upon identifying forms of care that can be offered on a long-term basis, payers may find that they have to make adjustments to solidify these benefits.

For example, UnitedHealthcare has added the home as a qualified site of care to make remote patient monitoring and virtual care more accessible.

“Moving forward, we will continue to recognize the home as a qualified site of service,” said O’Shea. “This helps make it more convenient for millions of members to remotely access their own healthcare providers for certain services, including primary care physicians and specialists, outside of the provider’s office. This is an important change designed to help encourage members and care providers to continue to use virtual care, even after the pandemic wanes.”

How do we determine reimbursement for telehealth and virtual care services?

The ongoing conversation about how to properly reimburse for telehealth services will be a huge component of permanently integrating telehealth as a mode of care alongside provider offices, hospitals, and other physical sites of care.

Traditionally in this debate, providers are portrayed as universally advocating for parity between reimbursement for telehealth and in-person care while payers, by and large, resist payment parity for cost reasons.

However, Epple pointed out that there is actually more nuance to both the payer and provider views than it might appear initially. Leveraging overlapping incentives with virtual-only care providers can help payers move the conversation forward in at least one area of care.

“Brick-and-mortar providers in general are probably more likely to want payment parity or relatively close to payment parity simply because they do have likely higher input costs for running their clinics and offices, but also may be seeing the patient in person as well as virtually,” Epple said.

Providers who work primarily in-person are going to be using CPT and HCPCS codes and prices that are already well-established for their in-person services. If payers try to negotiate lower rates with in-person providers, these providers are acutely aware of how much money they are losing in contrast to their in-person rates.

Strictly virtual providers, on the other hand, may be more open to novel payment arrangements.

Platforms like Teladoc and Doctor on Demand, Epple noted, might have more flexibility to adopt compensation structures that allow for a per member per month payment rate or a subscription fee model.

Nearly every payer has leveraged this type of strategy to some degree, but Epple anticipated that those novel arrangements with virtual care providers will expand.

Setting novel payment arrangements with virtual-only care providers not only has the potential to decrease healthcare spending, but it can also function as a known expense for payers at a time when future spending is uncertain.

As payers wait to see how COVID-19 affects utilization, whether a second wave will arise, and COVID-19’s impact on premiums, at least the bill for their virtual care advanced payment model will be predictable.

Ultimately, data related to long-term telehealth usage will be the main factor that settles the reimbursement debate.

“The data is still being developed to understand what the actual cost offsets or what the right payment rate looks like for telehealth. That’s something that we’ve talked to both plans and providers a lot about,” said Epple. “If there is any silver lining to 2020 in the last six months, I do think a lot of it is going to be the fact that payers are now generating a lot of data about how their chronic care patients have access to services via telehealth.”

Thompson agreed that now is the time for payers to lean on value-based care arrangements to incentivize telehealth as an essential care delivery platform.

“If payers prefer providers that provide the full suite of support that their members are looking for, the providers will go there,” said Thompson. “The problem often isn’t that providers aren’t willing to go there, it’s that the incentives are locked in to an old way of thinking and not what the new environment could be.”

Primary care telehealth in particular would benefit from a population-based, prepaid model, Thompson noted.

“If you don’t pay on a fee-for-service basis, you make smart decisions on how to take care of patients,” he pointed out. “That empowers providers to think in a more patient-centered way about what they actually need to see that patient for, and how they can conveniently provide the care.”

This debate will likely need to be decided by the end of the year, Thompson projected. As utilization drops back to more stable levels, payers are letting their telehealth waivers expire. When those waivers are no longer in place, the conversation about reimbursement will naturally come to a crossroads and the industry will have to make a decision.

“One of the positive things about telehealth is that it’s technology-based,” Thompson added. “Technology does allow us to integrate more systematic measurement, more systematic checks and balances into the system. We should take advantage of that. There’s no reason that virtual care couldn’t be more standardized and effective care.”

While the data is still being developed regarding the actual cost benefits of more widespread telehealth utilization, as Epple indicated, there is no doubt in O’Shea’s mind that telehealth is something UnitedHealthcare members want.

In fact, during the pandemic, the nation’s favorability towards telehealth rose, particularly among seniors who, historically, have been a difficult demographic to engage with telehealth.

Over three-quarters of seniors who used telehealth said that they would do so again in the future, according to a study on behalf of Better Medicare Alliance. More than nine in ten reported that they had a positive experience.

Thus, as UnitedHealthcare follows state and federal guidelines around virtual care reimbursement and the dust settles on that subject, O’Shea said that the payer will continue to encourage member utilization of telehealth tools.

“Continuing to drive the adoption of virtual care will be aided by multiple strategies, including the use of pro-consumer health plan designs that may make this technology more affordable, convenient and simple; consistent and customized communications that may help people identify virtual care resources and take more steps to use it; and supporting care providers so they are better able to make virtual care a key part of their practices,” said O’Shea.

As payers seek to permanently integrate telehealth into their healthcare delivery strategy, solidifying what care services most benefit from telehealth and how much they should reimburse providers will be challenging but pivotal.